Years ago, a friend and I compared our reactions to a powerful novel whose crude, wounded and realistic characters were caught in a perpetual cycle of brokenness. When she reached the end, my friend hurled the book across the room. I had a similar visceral reaction, absent any paper missiles.

Years ago, a friend and I compared our reactions to a powerful novel whose crude, wounded and realistic characters were caught in a perpetual cycle of brokenness. When she reached the end, my friend hurled the book across the room. I had a similar visceral reaction, absent any paper missiles.

The difference: she loved it; I loathed it.

We probed our love-hate responses. My friend felt that the story, while fictional, helped her to better understand the multi-generational dysfunction that plagues some families. She appreciated the truth that some stories just don’t have neat, happy endings. Her empathy with the characters and recognition of the book’s truths trumped my queasiness with its raw finale.

I sometimes hear readers say, “Why read fiction? I want to read about things that are real.”

What that argument misses is how fiction, while not factual, often holds real truths.

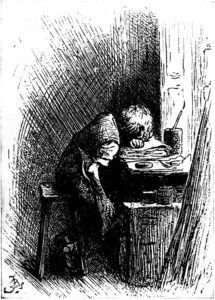

Insights into Charles Dickens beloved classics and characters are found among the hardships and truths from his own childhood:

Insights into Charles Dickens beloved classics and characters are found among the hardships and truths from his own childhood:

“Following his father’s imprisonment, Charles Dickens was forced to leave school to work at a boot-blacking factory alongside the River Thames. At the rundown, rodent-ridden factory, Dickens earned six shillings a week labeling pots of “blacking,” a substance used to clean fireplaces. It was the best he could do to help support his family…He felt abandoned and betrayed by the adults who were supposed to take care of him. These sentiments would later become a recurring theme in his writing.”

In her memoir, “Two or Three Things I Know for Sure,” Dorothy Allison, whose novel “Bastard out of Carolina” was a 1992 National Book Award finalist, described writing about uncomfortable truths, “I know the use of fiction in a world of hard truth, the way fiction can be a harder piece of truth.”

The desire to ban certain works of literature is brought on not by the facts they contain, but instead by their essential truths. In “Reading Lolita in Tehran,” Azar Nafisi wrote of her experiences and discussions teaching banned literature—including classics such as “The Great Gatsby,” “Pride and Prejudice,” and of course “ “Lolita”—to a group of women in the years following the Iranian revolution: “Do not, under any circumstances, belittle a work of fiction by trying to turn it into a carbon copy of real life; what we search for in fiction is not so much reality but the epiphany of truth.”

Part of what good stories, including fiction, does is make us think. This may be through exercising our imagination, critical thinking, or emotional thought. In an earlier blog, “Novel Therapy,” I wrote of the potential therapeutic value of literature and referenced how stories help us feel more connected, view our failures with less self-recrimination, and enhance our perspective and empathy for ourselves and others.

Award-winning author Ann Patchett wrote of fiction, “It gives us the ability to feel empathy for people we’ve never met, living lives we couldn’t possibly experience for ourselves, because the book puts us inside the character’s skin.”

Empathy is a powerful gift. When a book’s truths stir us to curiosity, desire, laughter, tears, or even an enraged lob across the room—it is worth the read.

“It’s in literature that true life can be found. It’s under the mask of fiction that you can tell the truth.”

Gao Xingjian